Here in El Salvador, Life is Worthless

The Monument to Truth and Memory shares over 28,000 names of people who were killed or disappeared during El Salvador’s civil war // Photo Credit: Jeff Peak

BY GUEST BLOGGER | August 20, 2014

written by: Matt Cuff, National Advocacy Office of the U.S. Jesuit Conference

Fr. Ignacio Ellacuría SJ, president of the University of Central America (UCA) during the Salvadoran Civil War, had an incredible gift for discerning the uncomfortable truths behind complex events. This gift would lead to his assassination in 1989. In an essay on what Ellacuría meant to him, Fr. Gustavo Gutierrez, a friend and colleague, recalls that “In the face of the horrors of those years, Ignacio used to say with shock and pain, ‘Here in El Salvador, life is worthless.’”

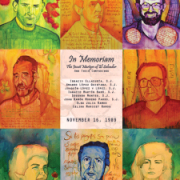

I’m so grateful to the Ignatian Solidarity Network for inviting me to take part in their recent delegation to El Salvador, commemorating the 1989 assassination by a U.S.-trained battalion of the Salvadoran army of Ellacuría, his five Jesuit brothers—Amando López, Joaquín López y López, Ignacio Martín-Baro, Segundo Montes and Juan Ramón Moreno—as well as their housekeeper Elba Ramos and her daughter Celina. Our delegation experienced firsthand the legacy of these men and women who worked tirelessly for justice in El Salvador and paid the ultimate price.

After spending eight days visiting the UCA, taking part in Mass in the chapel where these martyrs are buried, listening to poor families in the countryside share the challenges they faced during their country’s civil war, and learning from experts on the ground about current challenges in the region, I’m tempted to agree with Fr. Ellacuría’s assessment of Salvadoran and Central American reality.

El Salvador’s civil war was brutal. The UN Commission on Truth for El Salvador, which was established to set up to investigate human rights abuses during the war, found that the vast majority of the estimated 75,000 people who died were innocent and unarmed men, women, children, and even infants. Government forces, especially the U.S.-trained Atlacatl battalion, participated in dozens of documented massacres including the infamous massacres at El Mozote, Rio Sumpul, and the UCA murders. The Commission concluded that the Salvadoran government and military were at fault for 85% of the human rights abuses during the war.

Violence didn’t stop when the UN-brokered peace accords were signed in 1992. According to a United Nations report, El Salvador ranks fourth on the list of most violent countries in the world. Neighboring Honduras and Guatemala are ranked first and fifth respectively. Additional reporting notes that ninety-five percent of murders go unpunished in El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. One father told our delegation of the horrific moment when his missing son was returned to him in a trash bag, a mere pile of skin and bones that the organ traffickers he fell victim to couldn’t use.

Should we be surprised that today almost two thirds of youth migrants from the region cite violence as the reason they are fleeing their homes? In cases not specifically driven by violence, youth cite family, usually a parent, in the United States, or a life filled with poverty and few legitimate opportunities for meaningful employment as reasons for leaving. What is our solution to this violence—both physical and economic?

In a talk he gave less than a year before his assassination in 1989 Ellacuría offered his thoughts: “The United States has a solution, but, in my opinion, it is a bad solution, both for them and for the world in general. In Latin America, on the other hand, there are no solutions, only problems; but as painful as they are, it is better to have problems than to have a bad solution for the future of history.”

Read in light of the twelve year civil war in El Salvador, Ellacuría’s comments are spot on. The United States provided $1.5 million per day to the Salvadoran government, to a country whose population has only just reached 6.3 million. This funding was used to directly finance thousands of murders. Instead, the U.S. government could have pressed for fair elections, modest land reform, and placed human rights conditions with teeth on all aid to the region. A father in rural El Salvador shared with me the simple reasons for joining the FMLN, the guerrillas, “I only wanted enough land to feed my family and send my kids to school.”

Our solutions to today’s problems aren’t much better. Rather than welcome Central American children fleeing violence, a number of our elected officials prefer accelerated deportations of these kids. U.S. programs like the Central American Regional Security Initiative (CARSI) often fund corrupt police forces accused of murdering young people they suspect to be gang-members or working in collaboration with drug cartels to supplement their meager salaries. The United States spends $18 billion per year on immigration enforcement.

Meaningful solutions to the current crisis in Central America will come from Central Americans themselves. Holistic approaches to gang violence, like the Fe y Alegría program, can lead to long lives of hope rather than a short lives in a gang. A number of prosecutors’ offices in Central America that have demonstrated the courage to tackle state corruption and impunity. CARSI funding could be prioritized to strengthen these judicial systems. We can also take note of the courage poor communities, like the village of Carasque in which I stayed, have in challenging multi-national mining corporations that would pollute their rivers, forcibly displace them from their homes, and intimidate or kill anyone who tries to organize.

On our second day in El Salvador, our group spoke with Fr. Jon Sobrino SJ, who would have been killed with his friends had he not be speaking at a conference out of the country. He told us that his friend Ellacuría would frequently say to him, “It is not us who are going to save the poor, it is the poor who will save us.” This, Ellacuría meant quite literally. The best solutions, the most sustainable solutions, the solutions that will change this region and the world for the better—not the band aids that our government is so fond of offering—will come from Central Americans themselves. We only need to listen and open our hearts because, maybe, here in El Salvador life isn’t worthless.

Matt Cuff is a Policy Associate in the National Advocacy Office of the U.S. Jesuit Conference in Washington, DC. Matt is also an alum of Scranton Prep and Fordham University.

Matt Cuff is a Policy Associate in the National Advocacy Office of the U.S. Jesuit Conference in Washington, DC. Matt is also an alum of Scranton Prep and Fordham University.

Matt Cuff is the senior policy advisor of the Advocacy Office of the Jesuit Conference of Canada and the United States. He earned his B.A. in theology from Fordham University in the Bronx, New York, and is a graduate of Scranton Preparatory School in Scranton, Pennsylvania.

Excellent article!

The martyrdom at the UCA in San Salvador had a great impact on people around the world.

For instance, Sue Wheaton got involved in the movement to end U.S. military aid to the death-squad government of El Salvador when six Jesuits and two women were assassinated at the Central American University (UCA) in El Salvador in 1989.

Along with some Vietnam Vets, she was arrested for speaking out during a hearing in the U.S. Capitol.

See my video: Wheatons Part 4 Sue Wheaton on El Salvador

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CWxmHZL2Tr0

Peace,

Joe Mulligan, SJ

Managua