Good Friday: Comprehending the Loss of a Child

Over these past 40 days of Lent, I’ve been doing a lot of reflecting on one of my greatest un-freedoms: fear. I wouldn’t say that fear controls me, but I would certainly say that fear is my enemy. It’s what I offer up to God whenever I need forgiveness, because more often than not the root cause of my failure to love can be traced back to fear: fear of rejection, fear of offending, fear of ridicule, fear of failure, fear of death. I am afraid of losing my loved ones, afraid that my children will be hurt, afraid that they’ll repeat any of my most painful mistakes.

Over these past 40 days of Lent, I’ve been doing a lot of reflecting on one of my greatest un-freedoms: fear. I wouldn’t say that fear controls me, but I would certainly say that fear is my enemy. It’s what I offer up to God whenever I need forgiveness, because more often than not the root cause of my failure to love can be traced back to fear: fear of rejection, fear of offending, fear of ridicule, fear of failure, fear of death. I am afraid of losing my loved ones, afraid that my children will be hurt, afraid that they’ll repeat any of my most painful mistakes.

Sometimes it takes great effort for me to refrain from shouting “Be careful!” to my sons when they’re scaling the jungle gym or climbing the highest ladder at the playground. I’m always wondering how to teach them to be kind and hospitable while also making sure they know how to keep themselves safe in unfamiliar situations. I don’t want my children to grow up being afraid to take risks. I want them to set their sights on a goal and be willing to struggle for it, to venture into unexplored territory and open their minds and hearts to all the world has to offer, to put themselves out there for friendship, love, and justice. And at the same time, I don’t ever want them to suffer.

I know this is impossible, of course. No one makes it through this life without suffering, yet no parent wants to see his or her child in pain. Just a few weeks ago, I had an experience that brought this tension to life for me in a profound way. I was assisting with a 5-day silent Ignatian retreat, and during a reflection on Christ’s suffering one of my fellow directors encouraged us to walk down a hall in the retreat center to observe these beautifully unique paintings of the Stations of the Cross. The artist painted some as though looking through the eyes of Jesus, and others were created through the lens of an outside observer. All of the paintings are vibrant with color, despite their grim subject matter. My colleague instructed us to choose one painting that really resonated with us and spend some time contemplating it.

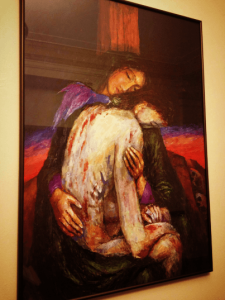

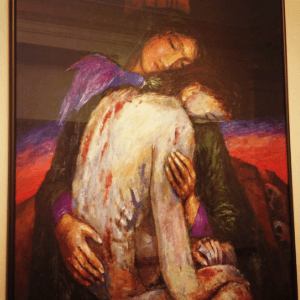

As I walked the halls, I found myself drawn first to the depiction of Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane, flung over a rock in desperation while the disciples doze in the foreground. As I made my way up one wall and down the other, though, I came to a painting that instantly had my gut churning with unease: Mary, sitting at the foot of the cross against the backdrop of a black sky, tenderly cradling her son in her arms after his pale, mutilated body has been removed from the cross. My reaction to this painting was so visceral that I was tempted to just keep walking, to ignore whatever it was that was being stirred up in me. It occurred to me, though, that a reaction this strong was rooted in some interior movements that I probably needed to pay attention to.

When I forced myself to engage a bit more with the painting, I realized that I found it so disturbing because of the way Mary is holding Jesus. It isn’t like the Pieta, where he’s sprawled horizontally across her lap. He’s curled up against her vertically, his head on her shoulder, eyes closed, like a sleeping child. It’s the same way my children like me to hold them when they’re tired, sick, or in need of comfort. For the briefest of moments I imagined what it must have been like for Mary, holding her lifeless adult son the same way she held him when he was a warm, chubby, snuggly toddler. The thought was so painful – so inconceivable – that I simply couldn’t hold on to it. And what a luxury that is for me. There are many parents who can’t relinquish the horror of losing a child from their imaginations because they have lived it – they are living it.

Mary was a young, unmarried girl, visited by an angel who tells her that she’s to give birth to a son destined for greatness. There are signs of foreboding from the very beginning: the family is forced to flee to Egypt to avoid Herod’s murderous envy. Simeon tells Mary that “a sword will pierce her own soul” (Luke 2:35). As Jesus grows into an adult, these hints of darkness become even more real. Mary must have known that Jesus was courting danger when he began to attract the attention of the authorities during his ministry. Her gut must have been churning with unease as she watched him continue to put himself out there for friendship and love and justice. And yet – as far as we know – she didn’t try to convince him to quit, or dissuade him from being the person God called him to be. Somehow she was able to step back and allow her son to live his own life in spite of the incredible risks involved. Mary was a woman whose life went from ordinary to extraordinary with a simple “yes.” She responded to God’s call, and her life was changed for better and for worse. She is the opposite of risk-averse.

This Holy Week, as we prepare once again for light, love and hope to triumph over darkness, sin and death, my prayers are directed in a special way to Mary the mother of Jesus. I’m praying for parents who have lost children, aware that I cannot begin to comprehend the depth and breadth of their suffering. I’m praying for freedom from fear, and for the ability to help my son’s grow into the people God calls them to be in spite of my worries about their safety, health and happiness. I’m praying for the ability to let go when I need to, for the courage to allow them to learn from their mistakes, for the grace to let them experience the gamut of emotions that give life its richness and depth. Their lives will not be without suffering, and I know that I will suffer when I see them in pain. But they will have plenty of delight in their lives, too, which I will celebrate and cheer. This Holy Week, I’m praying to Mary for my heart to be broken open, my arms stretched wide, with a grateful “yes” on my lips to God for this joyful, heartbreaking, wondrous journey that is parenthood.

Emily Rauer Davis is a graduate of the College of the Holy Cross (99) and Weston Jesuit School of Theology (03), and is also an FJV (Fresno 99-00). She’s worked at several Jesuit institutions and apostolates, including Holy Cross, Loyola University Maryland, Seattle University and the Ignatian Spirituality Center in Seattle. Emily and her husband Andrew live in the Boston area with their two boys, Michael (age 4) and Peter (age 2).

My beloved son was 32 when he died from AIDS. I was devastated and pretty inconsolable for some time. In the week following the funeral a good priest friend stayed with us as a supportive person. One day I said I could relate more to Mary’s suffering in the loss of her son. The priest said I should not be comparing Greg and I to Mary and Jesus. I shut down and could not wait for him to leave. Our wounds are human wounds just as Mary and Jesus wounds were human wounds. Only Jesus and Mary were my true comforters during that time until I finally sought counseling to fully grieve and heal. That was 32 years ago, and when grief surfaces at times, Mary, Jesus and I have a good cry together as we recall, converse and share our woundedness.