For that meal, the issues we think of when we hear “township” or “ghetto” took a backseat. We crowded together, laughing and eating our kotas, big sandwiches full of meat and french fries. We marveled at how awesome, albeit unusual, our friendship was given our differences.

Just before we were about to leave, Scott leaned over to share the last of the cream soda. He made a point to carefully pour it out as equally as he could, and I couldn’t help but think about the moment in the Catholic Mass when the gifts are prepared, bread broken, and wine poured. I would like to think Christ was present in this communion of soda and sandwiches, and I am not sure if anyone would have felt the same way if the focus of our meal was on what I thought my friends might be lacking in their lives. Frankly, this meal made me think that we do a disservice to anyone we care about if we treat them like a collection of problems.

This is not an excuse for inaction, in fact, it is quite the opposite. I believe our world needs immediate action and concrete steps toward peace, justice, and freedom. It is no coincidence, however, that our greatest champions for these virtues were motivated by powerful “being” moments. Nelson Mandela’s imprisonment is one such example of forced “being”. Twenty-seven years in prison matured his vision for South Africa, according to the staff at the Nelson Mandela Foundation. Not only was his imprisonment an astounding personal sacrifice, it also helped him revolutionize his vision for South Africa, turning it into the reconciliatory goal of a rainbow nation for which he is famous.

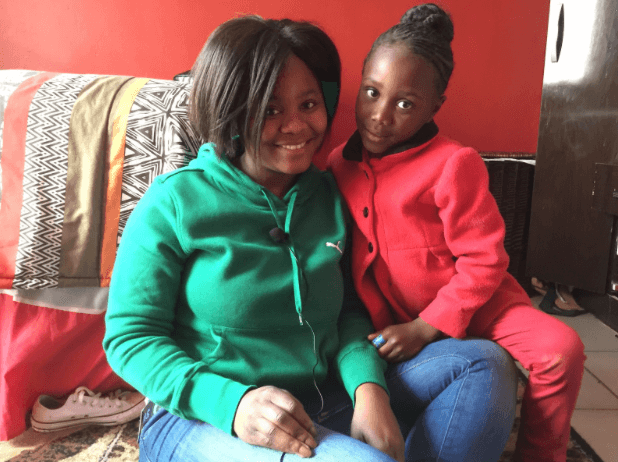

Nelson Mandela’s office