Flashing, rattling, booming. The streets of Soweto flooded with life—a cleansing baptism to a long and dusty month of dryness—as rain blessed us on our final days in South Africa. The sound of rain against zinc roofs contrasting with the low roaring of thunder created a djembe rhythm. Soweto sung along. The heavy downpour gave the skies a cool ocean freshness that hummed an aura on the horizon where brown musk and smoke had once polluted the skyline. There was no more burning. We could finally breathe in semi-fresh air. It was a new day in Soweto.

On our final day in Soweto, crisp blue skies—newly cleansed by the winter storm—gave a refreshing light to Soweto. Yet, we were still experiencing grayness. We were still still struggling between the notion of “being” and “doing” as we reflected on our past six weeks, and this continues to weigh on our mind. To many people, the question, “What are you doing?” is answered by a dollar figure or “donating to the Africans,” as someone once told us. Rather, after our time in Soweto, we would like “doing” to become more mutual. We hope that doing becomes being when there is a purpose that allows someone to become more fully oneself. This rang true when we visited the Nelson Mandela Foundation for an event on “fallism” several weeks ago. When asking one of our friends at the Foundation for advice on how we can best use our studies and education to make a difference in the world, she responded by saying, “Honey, we’re not really looking for your help.” Later on in the event, we talked to Jay Naidoo, former Minister responsible for the Reconstruction and Development Program and Minister of Post, Telecommunications, and Broadcasting under Mandela’s office. After asking him for advice, he said something along the lines of, “Well, you didn’t say anything at this event. You just listened. This is the first time I’ve been at a conference with Americans where that has happened. Maybe that’s a sign.”

Being in Soweto has been difficult. Carrying stories of depression, death, suicide, gender inequality, and family abuse have weighed heavy on our hearts. In a township of endless burning, these dark stories only added to the grayness of our time in Soweto. Compared to our last two trips to Soweto, we have had quite a different response to our experiences. This time, our reaction hasn’t just been gratitude or hasn’t just been relief over the psychological distance and yearning to “return home,” but rather has led to a greater focus on and realization of the relationships we carry with us. Whether it is economic relationships, social relationships, or spiritual relationships, we have begun to question how the way we are living affects those we are in relationship with, whether we realize it or not. How are my actions affecting others, both directly and indirectly? Am I ignoring these relationships? When does my presence become mutual when fostered in a relationship?

The theme of relationship was present when we talked to Tshegofatso. Throughout our conversation, Tshegofatso kept on looking at our fancy GoPros and “western” clothes, using his eyes to tell the story of a childhood of neglect and family abuse. When we asked him how we should bring the stories of Soweto back with us to the U.S., Tshegofatso said, “Be real to them. Tell them exactly what you have experienced. Tell them the truth. Tell the people to do something. Maybe to help, but not always financially. It’s not really about money. It is often about knowledge and care…or just dignity. When those tourists come to Soweto sometimes I wonder if they really know what life is like here. Listening is a skill. How can we both get better at that skill?”

Subscribe to Simunye Project

Simunye Project Posts

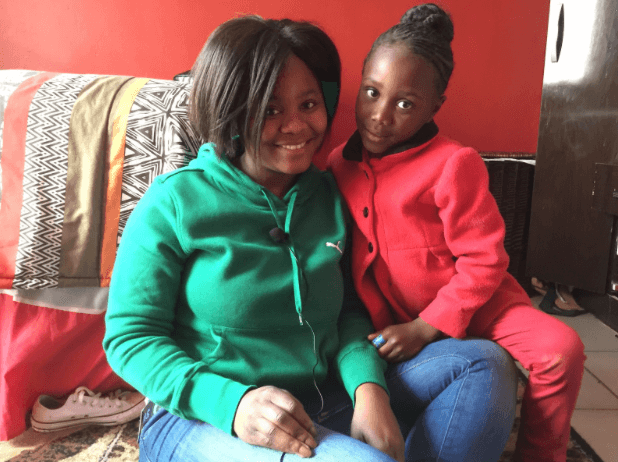

Being A Mother For And With Others: Thabisile’s Journey Of Motherhood in South Africa

https://ignatiansolidarity.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Screen-Shot-2016-07-22-at-12.49.43-PM.png

1048

1500

The Simunye Team

https://ignatiansolidarity.net/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/ISN_Color_Transparent_Large.png

The Simunye Team2016-07-22 13:25:562017-02-05 20:23:28“Im sorry. Goodbye.” Defining Family for Lesedi

https://ignatiansolidarity.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Screen-Shot-2016-07-22-at-12.49.43-PM.png

1048

1500

The Simunye Team

https://ignatiansolidarity.net/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/ISN_Color_Transparent_Large.png

The Simunye Team2016-07-22 13:25:562017-02-05 20:23:28“Im sorry. Goodbye.” Defining Family for Lesedi