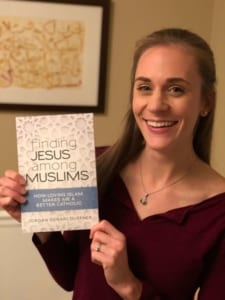

Finding Jesus Among Muslims: A Q&A with Jordan Denari Duffner

BY ISN STAFF | June 14, 2018

ISN recently spoke with Jordan Denari Duffner, author of Finding Jesus among Muslims: How Loving Islam Makes Me a Better Catholic. While a student at Georgetown University, Duffner spoke from the main stage at the Ignatian Family Teach-In for Justice (IFTJ) on dialogue with Muslims. She has continued to join ISN at IFTJ as a breakout presenter through her work with the Bridge Initiative, a research initiative on Islamophobia based at Georgetown University where she previously worked as a research

Can you explain how this book came to be? How and when did you find yourself as a voice for Christian-Muslim relations?

In many ways, the book emerges from my own experience. I have studied Islam and Islamophobia, and have also lived and worked among Muslims both in the United States and in Amman, Jordan in the Middle East. The book is a call for Catholics and other Christians to engage in dialogue with our Muslim brothers and sisters. In it, I talk about how dialogue doesn’t draw us away from our faith, but how it can deepen our relationship with God, which has been my experience.

I also hope the book fills a need. When I worked as a research fellow for the Bridge Initiative, I spent much of my time doing research on Catholic media portrayals of Islam. I realized that there were very few books about Islam out there for Catholics that reflected the approach the Catholic Church wants us to take. I hope my book can serve as an invitation for Catholics—both students and adults—to engage in the positive relationships the Church calls us to.

What does the Catholic Church have to say about interreligious dialogue?

The Catholic Church believes that interreligious dialogue is a central element of living our faith. The Church talks about four types of interreligious dialogue in which we can and should participate. The most important of these is the “dialogue of life,” where we simply interact and share our lives with those of other faiths in the ordinary settings of work, school, and neighborhood. Dialogue is not primarily about talking or discussion; it’s about encounter—seeing another person face-to-face, for who they are—really getting to know them. I also think it’s important to emphasize that the Church says that we “hold Muslims in high regard.” This attitude of respect, hospitality, and good will should guide us and be our default position toward all people of faith.

Pope Francis prays with Istanbul’s grand mufti Rahmi Yaran during a visit to the Sultan Ahmed Mosque, also known as the Blue Mosque, in Istanbul Nov. 29. (CNS photo/L’Osservatore Romano via Reuters)

Can you share a personal story of how you have witnessed the power of interreligious dialogue effect change, either on a small or large scale?

When I was an undergrad and organized dialogues between the Catholic and Muslim students at Georgetown, we had Muslim students join the Catholics for a scripture reflection gathering in the chapel, and we took the Catholic students to a Qur’an study group in the Islamic prayer room on campus. It was the first time many of the Catholic students had been in a Muslim religious setting, and I think it helped break down many of the stereotypes they may have had. The gathering in the chapel was a powerful moment of unity, too, where we were witness to the deep spiritual yearnings we all have, whether Catholic or Muslim.

The author writing children’s names in Arabic calligraphy at a Holy Land festival in Washington, D.C. [Jaclyn Lippelman]

Islamophobia is prejudice and discrimination that targets Muslims and people who are perceived to have an association with Islam. Like other forms of racism and bigotry, Islamophobia exhibits itself in diverse ways. Many of us may have heard of a bias crime happening in our city or local community—like a Muslim being yelled at with a hateful slur, a mosque being vandalized, or a child being bullied at school. The FBI tracks anti-Muslim hate crimes like these and the data shows a sharp increase in anti-Muslim crimes, especially violent assaults, in the last few years.

As your question indicates, Islamophobia goes beyond blatant hate crimes. Many of us hold onto stereotypes about Muslims that impact the way we treat them in our daily lives. Studies have shown that many Muslims experience discrimination in applying for jobs, and numerous Muslim doctors, for example, have had patients who refuse treatment from them in the hospital. In the classroom, Muslim students are often called on to speak for their entire community, as if Islam is a monolithic religion and they can speak for all Muslims. Islamophobia also exists in our politics and government policy. Politicians use fear of Muslims for political gain during elections, and on both the state and national level politicians have sought to (and in some cases succeeded) enact policies that target Muslim communities. Stereotypes about Muslims are also commonplace in our media. Muslims are portrayed as uniquely violent, oppressive to women, and intolerant of diversity, and these stereotypes often appear in news coverage or entertainment media when Muslims are discussed.

One thing I should also add is that Islamophobia doesn’t only impact Muslims. Many non-Muslims, including Christians, who are mistaken for Muslims have been attacked violently. People who have dark skin, wear turbans, or who speak foreign languages are often ascribed the same negative traits that Muslims are. All of these things are elements of Islamophobia.

How is the reality of Islam and the picture painted by our media and political rhetoric in the U.S. different?

In the media and in politics, Islam is mistakenly portrayed as a religion that is very monolithic, as if there is only one way of being Muslim. But Islam is very diverse, and Muslims live all over the world, not just in the Middle East. The four most populous countries with predominantly-Muslim citizenry are in Asia. In the United States, 20% of Muslims are Black. Our media often doesn’t display this diversity, nor the beauty of the Islamic tradition, like its art and architecture.

Jordan Denari Duffner

As a Catholic, how has Islam and friendship with Muslims deepened your faith? How can these two religions be mutually beneficial to one another?

Muslims are friends who undertake the journey of the spiritual life with me. Our conversations are not usually about coming to firm answers on big questions, but about the common journey and struggle of living as people of faith. I love the metaphor of interreligious dialogue as “digging a well to God together.” It’s a metaphor that a Catholic monk and his Muslim friend in Algeria used to talk about dialogue, and to me, it conveys the idea of working together to discover and be encountered by the God who we both seek to serve but who doesn’t belong to either of us. Dialogue often inspires us to live our lives in new ways. My encounters with Muslims and Islam compelled me to dive into Ignatian prayer, and develop a deeper spiritual life within my own Catholic tradition.

How does a worldview that looks at justice through the lens of faith manifest in the Muslim community? How is it similar or different from the justice-minded Catholic community?

As I talk about in my book, the nexus between faith and justice is central to Islam. There are beautiful passages in the Qur’an that pair “spiritual” things like prayer right next to “social” obligations like serving the poor. One passage from the Qur’an reads: “Worship God and do not elevate anything at all to share His worship. Deal kindly with your parents and your kinsfolk, with orphans and the poor, as well as with the neighbor who is of your kin and the neighbor who is a stranger, with the companion beside you, and with the wayfarer and the slaves in your charge. God does not like the conceited and the boastful” (4:36). As we know from our own Christian tradition, faith and works cannot be separated, and the same is true for Muslims.

As a Jesuit-educated individual, can you draw parallels in Islamic and Ignatian spirituality?

One of the parallels I see between Islamic and Ignatian spirituality is the goal of giving yourself over to God’s desires for you. Catholics who are formed in Ignatian spirituality and Muslims seek to conform their lives to God’s will. I also think we both are dedicated to being “contemplatives in action”—being rooted in daily prayer while also working in our local community to make it a better place.

How has your Jesuit education prepared you for the work you’re doing?

My Jesuit education at Brebeuf Jesuit in Indianapolis and at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C. emphasized the importance of interreligious dialogue. I was fortunate to learn about other religious traditions in the classroom and meet people of other faiths. My Jesuit education also emphasized the importance of “vocation,” not just in the sense of marriage or religious life, but in the sense of what God is calling me to do in the world. I feel that my work in building up relationships and understanding between Christians and Muslims is a vocation God has called me to.

Watch Finding Jesus among Muslims: A new book by Jordan Denari Duffner

Human beings are a privileged lot blessed with the ability to dialogue.