Ahmaud Arbery: Responding as Educators to a Culture of Racism

BY BRIAN MARAÑA | May 16, 2020

How can educators respond to a culture of racism? How can we journey with students who carry the weight of racism?

I must confess that my first reaction was avoidance. It felt overwhelming. “Not again,” I said to myself. “I don’t even want to know.”

A friend who I deeply admire shook me out of this complacency through a social media post that said, “Calling all my allies, co-conspirators, and woke white friends, even if it’s just on Facebook to the carpet, the pulpit, the soapbox, the voting booth, the phone… can ya’ll hear me…because I sure CAN’T hear you…YOU DO NOT GET TO SIT ON THE SIDELINES…you witnessed, read about, learned of a MURDER and you are TOO QUIET for me.”

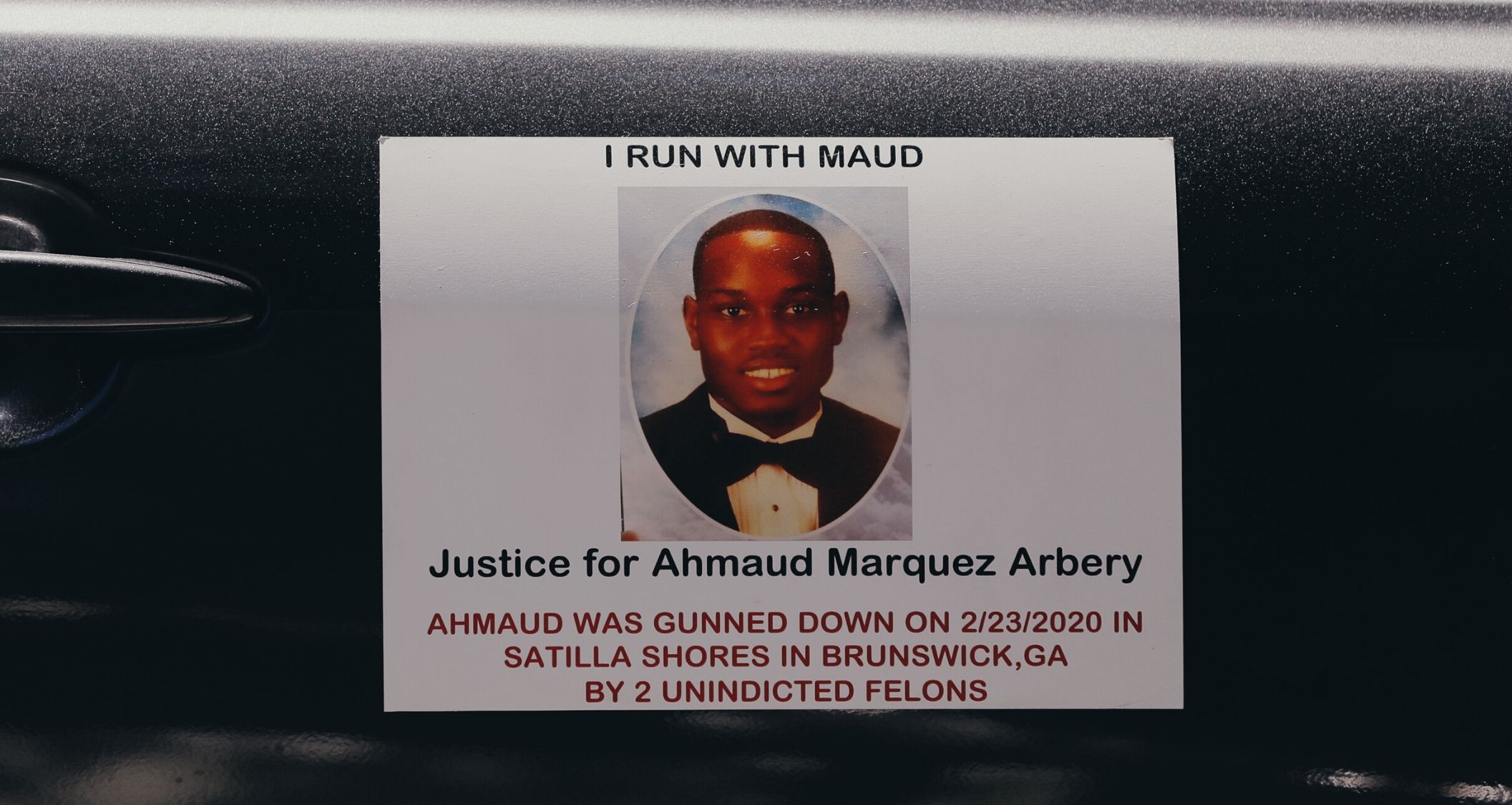

She was right. For all my desire to educate students for justice, I had been silent. I turned my attention to the news and learned about Ahmaud Arbery, who was shot and killed while out for a jog on February 23.

In disbelief, I posted on my own social media feed: “Racism is looking at an unarmed black man and presuming guilt, then looking at his white killers and presuming innocence. #AhmaudArbery.”

Over the weekend, a relative in the Philippines asked me about it. “Did that really happen? Are Americans really that racist? Are you safe where you are?” Thinking about all the wonderful people I know and love here, I instinctively said, “Yes that happened, but most Americans are not like that. There are just a few bad people. America is safe for the most part.”

But that’s not really accurate. America is safe relative to one’s skin color. That I sometimes forget that is a function of my own privileged place in America.

A FEW BAD INDIVIDUALS?

I suppose that it’s difficult to rid myself of the notions inculcated in me in elementary school: that we are all created equal; that Martin Luther King, Jr., solved America’s problem with racism; and that anyone can get ahead with hard work. Others do not want to rid themselves of these notions at all, as at least one prime time political pundit has declared that identity politics is a “sham,” and that racism isn’t a real problem in America. The argument goes that the playing field is level, and any injustice, though real, is the result of a few misguided individuals.

I’ve witnessed this type of thinking at Loyola Blakefield, as well, where I serve as assistant principal for academics. When faced with our own racist incidents, a number of well-meaning people said something along the lines of, “We have a good place here with good students. Let’s find the person who did it and kick him out. We’ll be fine.”

No one who expressed this sentiment was black.

If in fact, that sentiment were true, then our black students would have been just as shocked and outraged as their non-black teachers. They would have been just as eager to find the perpetrator and move on. But they weren’t. Black students and their parents expressed a similar sentiment: “Honestly, I’m hurt, but I’m not surprised.”

I do not mean this as an indictment on our community in particular, but rather as a way of saying that our community reflects the dynamic of American society. Our students of color face racism daily, in implicit and explicit ways, in their neighborhoods, in the hallways, in the locker room, and in the media they consume. They cannot escape it. To paraphrase Sterling K. Brown’s recent comments, it’s like they’re running with a mask that they can’t take off. They can’t breathe. And it’s exhausting.

This is why even two years removed from our own public racist incidents, students find such solace in our annual Neighbors Retreat. Often for the first time, students on this retreat find an outlet to share the burdens they have carried with them because of race. They come to realize just how tired they are.

RESPONDING AS A JESUIT SCHOOL

As Ignatian educators, how are we called to respond to a culture of racism? How can we journey with students who carry the weight of racism?

There may be few easy answers, but I know that we cannot afford to stay silent. While we may believe we are not being racist by simply enforcing our policies in a standard and consistent way, this does not add up to an experience of equality. We can’t simply “not be racist.” We must be proactive. We must do more. Here are a few things happening at Loyola.

Working out of our Ignatian Mission and Identity Office, director of diversity Bernie Bowers and associate Justin White have continued focus group discussions and have organized a number of justice-themed events, often led by students. These conversations have continued even in a time of distance learning.

Loyola English teacher Joe LaBella has started an anti-racism group, which aims not only to foster multicultural understanding but to drive against racist culture and practice. He recently shared a petition to continue the pursuit of justice for Ahmaud Arbery.

Theology teacher Allison Harmon is using resources from Teaching Tolerance to incorporate discussions about racism and current events into class.

In February, classics teacher Elizabeth Wise brought in an exhibit of Black Classicists arranged by Dr. Michele Ronnick, and history teacher Anthony Zehyoue teaches an entire class on Civil Rights.

At the institutional level, our assistant principal for faculty development John McCaul facilitated conversations last summer about Robin DiAngelo’s book, White Fragility. He was also set to run a full-day professional development session on racism, unfortunately canceled due to COVID-10. The day was to feature Ali Michael of the Race Institute and Natalie Gillard of Factuality, both of whom planned to help us build cultural competencies.

There is still much to be done, and our work will never be over. It may seem daunting, so let’s remember that the most important thing we can do is also among the simplest: to listen to our students of color. Let us give students an opportunity to speak, and let us be present to the weight of their pain. We may not have all the answers; in fact, we may have none. But in listening, we signal that our students’ voices—and their lives—matter.

Let’s pray that in being heard, our students may have a chance, however briefly, to breathe.

[Editor’s Note: This piece was originally published here by AMDG Eductor.]

Brian Maraña is an alumnus of three Jesuit institutions: Loyola Blakefield ’00, Loyola University in Maryland ’04, and the Ateneo de Manila University ’17. He has worked for The Beijing Center for Chinese Studies and for Xavier School in Manila, and he currently serves as the assistant principal for academics at Loyola Blakefield.

Human beings are made in the image and likeness of the divine – declare Holy Scriptures.