Human Rights Abuses and the State of Emergency in El Salvador

BY DANY DÍAZ MEJÍA | March 16, 2023

I visited Espíritu Santo Island in El Salvador in early February in order to follow up on the 22 men arrested between May and July of 2022. The men were arrested without probable cause under the government’s state of emergency that was declared in response to 87 people killed by gangs last March. I wrote about them for America Magazine last December—particularly that “the families of the men say they are not gang members or criminals and have been demanding that they be released.”

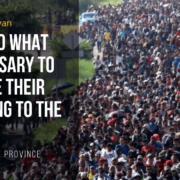

“The state of emergency suspended civil liberties like the right to legal counsel and family visits at detention sites,” I wrote for America. “By the end of November, Human Rights Watch and the Salvadoran human rights organization Cristosal reported that Salvadoran security forces had arrested over 58,000 people—most of them accused of being gang members or collaborators with gangs.”

To reach the island, I first rode a bus from San Salvador to El Triunfo port with a group of volunteers from the Center for International Solidarity (CIS), an organization that has been doing solidarity work on the island since 1998. The bus ride lasted close to three hours. We then took a 20 minute boat ride to the island.

Once on the island, we had to give our ID to a community guard and state our business. The Espíritu Santo Island is one of the few places in El Salvador with no gangs. The locals credit their community organizing for the safety of their home. About 15 years ago, they even got the government to install a police station on the island.

Afterwards, we met with community leaders, mostly women, and a group of young people that participate in the CIS scholarship program. At some point, I walked outside the community center to stand under the shade of an enormous tree. A woman, who seemed to be in her early fifties, approached me. Her name was Silvia and she wanted to tell me the story of her son, Saul Blanco.

Saul will be 36 years old this March. Since he was a child, he showed a great passion for soccer. Because of his talent and effort, he went on to participate in three beach soccer world cups. Silvia showed me videos of Saul playing beach soccer in which he looks fast and graceful. Silvia says that these videos started circulating in social media when Saul got arrested and that despite everything, she felt proud of how many people defended her son’s good name.

After his soccer career, Saul has dedicated himself to work for the cooperative on the island, mainly tending to cattle. In his spare time, he volunteers coaching soccer for the island’s youth. His mom took me to see the island’s soccer field, which is now covered in weeds.

Since Saul was arrested, Silvia travels every two weeks to the San Salvador prison where he is held, even though she is not allowed to see him. She worries because Saul has thrombosis, and without proper treatment, it could lead to clots traveling to his lungs or even death. She told me sometimes the guards make fun of her or scorn her because she doesn’t know how to read or write. Before I left the island, I promised her I would keep telling her son’s story.

Once in San Salvador, I kept thinking about a friend who told me that because of the state of emergency, she is now able to walk around her neighborhood for the first time since she was little. The gangs had caused so much pain in her community, but she felt that their stronghold had finally ended. I know the state of emergency is undeniably impacting gang structures, but I also know that, as Saul’s story shows, the human cost is high.

“The government speaks of human rights violations as collateral damage [to the anti-gang crusade], effectively inciting people toward vengeance,” Fr. José Tojeira, S.J., pastor of El Carmen Church in the Salvadoran city of Santa Tecla and a long-time human rights defender said in an interview with America. “The gospel calls us to pursue dialogue,” he said, “but the government has shut down that possibility.”

I also keep thinking of “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas,” a short story I read in my first year of college. In the story, Ursula K. Le Guin imagines a society free of violence with a dark secret: to keep the town peaceful, a small child must be beaten and degraded every night. Some townspeople cannot keep on living in the city once they learn its secret and leave. But the rest accept the horrible cost of their happiness. If we don’t tell Saul’s story, it would be as if no one in Le Guin’s story had to wrestle with the town’s secret.

The truth is that the mass incarceration of Salvadorans will have long term impacts we might not be even able to calculate today. But in the short term, we must wrestle with the policy’s fundamental challenge. We must decide if we can accept the torture of the wrongly imprisoned, in exchange for a respite from the gangs. In this decision rests a deeper one: the type of country El Salvador will become.

Dany Díaz Mejía grew up in rural Honduras. He graduated from John Carroll University in 2011 with a BA in political science. He also holds a MSc. in public policy and management from Carnegie Mellon University. From 2017 to 2020 he led the field operations of the Academy for Security Analysis. In the Academy he used his passion for evidence-based public policies to improve citizen security in Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador. He now works as an independent consultant for international development projects in Central America. In addition to his policy work, he is the author of the short story collection La Quebrada and a frequent writer on current affairs in outlets such as Gato Encerrado of El Salvador. He has also published in America Magazine in the U.S.

Human beings are made in the image and likeness of the divine – declare Scriptures.