BY TIM SEVERYN | May 17, 2018 | EN ESPAÑOL

At six and a half years old, Roberto* enrolled in kindergarten, a year behind his peers. Over the last 8 months, when he ought to have been learning to read and playing on the playground, he had instead been on the run with his papa, mama, and four year old sister, Marian—from the gangs in his home nation of El Salvador, from the human traffickers on the Guatemala-Mexico border, from the paid contractors on the Mexico-U.S. border looking to capture him and return him to the violence he had fled from months prior. He, like so many in similar situations, has experienced trauma.

[Sarnil Prasad via Flickr]

On Good Friday, the many faces of Christ crucified today covered the cross during veneration at Bellarmine Chapel in Cincinnati.

So here we are in 2018: Our government actively separating families like theirs for the sole purpose of discouraging other immigrants from coming, from fleeing violence in search of a better life.

Here we are: okay with locking up a 4-year-old child and her mother in an isolation ward, a shared solitary confinement; okay with a child sleeping on a tax-payer funded slab of a cot in a dark room without electricity.

Okay with so many families fleeing death threats for the better part of a year, only to be locked up by the designated “safe” country like they had committed a crime rather than been the victims of one.

We, the American people, have decided we are okay with this—so long as we’re secure.

But we, the Catholic Church, have decided we’re not okay with this.

In 2015, Pope Francis stood before some of the most powerful people in the world, the U.S. Congress, and declared: “Let us treat others with the same passion and compassion with which we want to be treated. Let us seek for others the same possibilities which we seek for ourselves. Let us help others to grow, as we would like to be helped ourselves. In a word, if we want security, let us give security; if we want life, let us give life; if we want opportunities, let us provide opportunities. The yardstick we use for others will be the yardstick which time will use for us.”

Bellarmine parishioners and members of the local immigrant community from Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador participate in a Share the Journey potluck meal.

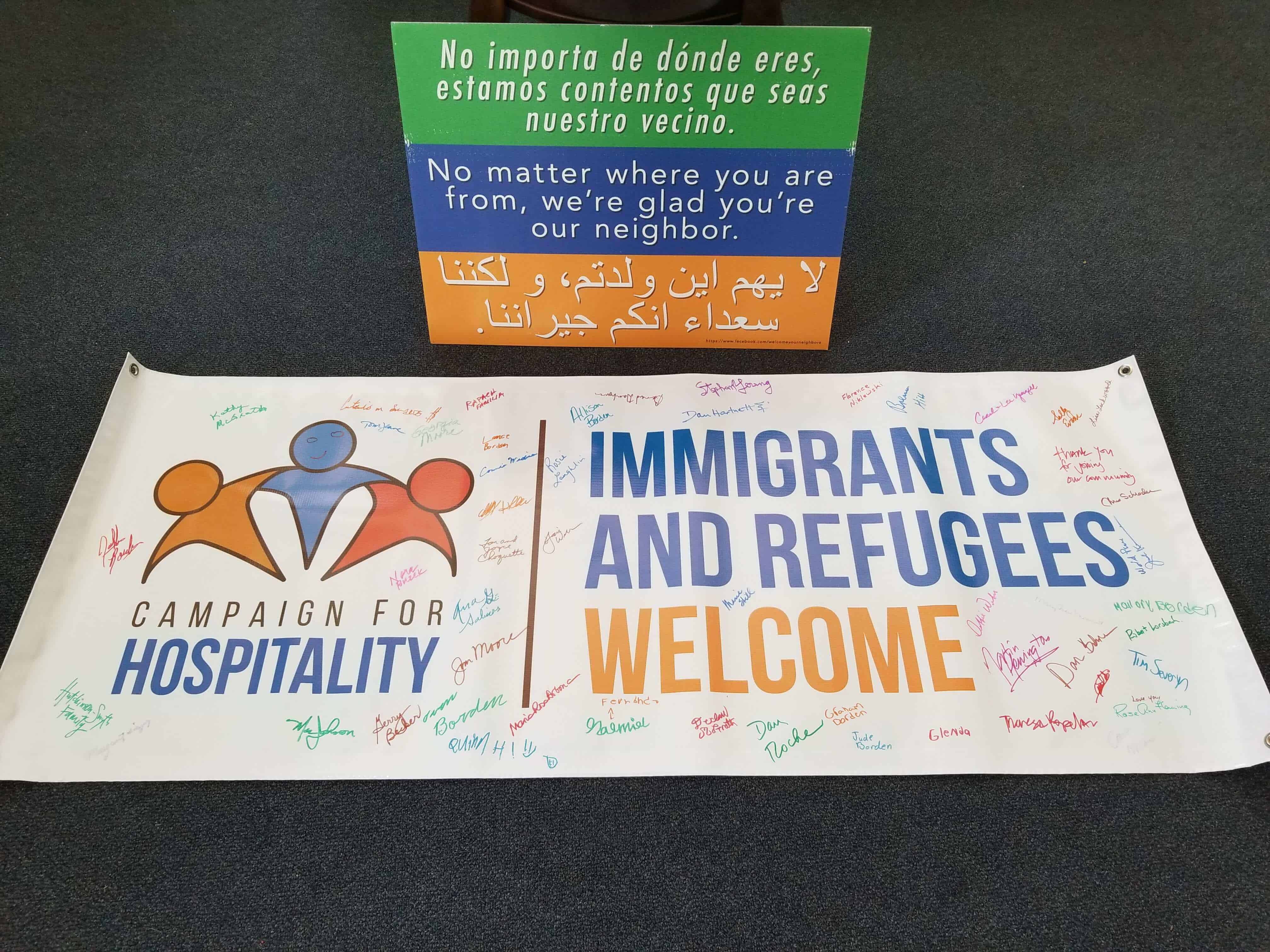

Last fall, Pope Francis invited all Catholic congregations across the world to join him in doing precisely this, launching a two-year campaign with Caritas called Share the Journey. In partnership with the Jesuits, the Ignatian Solidarity Network has launched a complementary effort known as the Campaign for Hospitality, with roots going back to an intercontinental Jesuit social ministry conference in the Dominican Republic last year. Among the attendees at that conference was Fr. Dan Hartnett, S.J., a longtime missionary in Peru and the current pastor of Bellarmine Chapel on the campus of Xavier University in Cincinnati, Ohio.

He returned from the conference on fire, quickly convening a group of parishioners and staff, including this author, a licensed social worker—around a simple question—What can we do? He wondered how we might begin to change the narrative around immigrants in our nation, or at least our community, to move from a story of criminalization to one of humanization.

At Bellarmine’s Share the Journey retreat for parishioners, Xavier University Theology faculty, Dr. Marcus Mescher, provides Biblical grounding for welcoming the stranger.

As one parishioner remarked, “We can’t continue to treat trauma survivors like criminals, to treat preschoolers like enemies of the state. If we throw people away, label them disposable, the excluded of the earth, we spit in the face of God. Jesus reached out to the most vulnerable, and said, I love you—let us eat together, let us have table fellowship.” Bellarmine’s table has grown, and we’ve gotten an inkling of the table size Jesus imagined, that God crafted to feed us all.

A member of Bellarmine’s Immigration Team welcomes attendees to a screening of the documentary Human Flow.

From that initial gathering, we have rapidly expanded encounters between our primarily white, university-bound, middle and upper-middle class parish with our immigrant neighbors. We have formed a parish Immigration Team that meets on a monthly basis and has sponsored a number of events in the realms of 1) Hospitality/Relationship Building; 2) Education; and 3) Advocacy. We’ve held a story-sharing event with 250 in attendance, listening to immigrant women and Dreamers share their trauma and triumphs. We’ve accompanied five women and their families as they have launched a catering business—with their first event our Feast of St. Ignatius Picnic for over 200 parishioners with fresh tamales, empanadas, and papusas—and much fellowship. We held a Share the Journey retreat with 100 parish leaders present. We’ve helped launch a new nonprofit in the city, Casa de Paz/House of Peace for Latina survivors of domestic violence. And we’ve recently helped the Ignatian Solidarity Network establish an Ohio-wide coalition of Jesuit works lobbying Senator Portman on the Dream Act.

But perhaps our deepest encounter, the one where we’ve truly shared the journey, expressing hospitality in the most radical sense of the word, of actually identifying with the suffering and becoming vulnerable ourselves in the process, has been with Roberto, Marian, Ella, and Luis, the family of four from El Salvador. We met them through the Kino Border Initiative, a Jesuit project in Nogales, AZ. KBI had contacted Bellarmine some months earlier with a simple request: We’ve got a family coming from El Salvador, could your parish take them in?

Father Dan wanted to do this, but he knew he couldn’t do it alone—his time in Peru meant he had a command of the language, but that wouldn’t be enough to carry a family from suffering to safety. Could our community move beyond the protected pavers and well-manicured lawns of Xavier University, beyond our own class privilege and white skin, towards true encounter? An informal survey of the parish, 750 households in total, revealed a smattering of Spanish-speakers, no more than 10 families. Was that enough? Could we make this work? Father Dan stood before the parish one Sunday, and directly said: “Bellarmine, we’ve been asked, can we respond? We’ve been called, how will we answer?” He put the question before each of us—and the response was tremendous, sacred, blessed.

Having gone through the Spiritual Exercises as a community, we were primed for discernment and ready for real encounter. We wanted to be a field hospital like Pope Francis urges, a church abounding in mercy and love. Within weeks, we received an outpouring of generosity. Solidly ¼ of the parish actively relayed a desire to be involved, to support financially, assist with medical or legal counsel, educate, provide meals, and more. When a bilingual family stepped up to host in their own home, we knew we were moving with God. In Fr. Dan’s five years with the parish, it was the greatest single activation he’d seen. And so we said yes: yes to God’s call, and yes to accompanying our migrant neighbors through trauma to health.

It has been a lot of work to support this family’s transition, and we’re still early in the process (pray for us!), but we are as far as we are because we made a conscious effort to work together in a move from the culture of indifference towards the culture of encounter, towards radical hospitality. When we strive to make ourselves vulnerable, God abides. When we strive to become painfully aware, and our fortresses begin to break down, we become something better than we were before conversion. When we hear our neighbors’ heartbeats’ distress in our own chests, and realize the blood they spill is our own blood, the abuse they endure is, in some part, our own—we can no longer turn a blind eye to their suffering. When this happens, we know in our depths that the Body of Christ is real, and everything is connected in God, shining like the sun. When this happens, we know the tears of a child are the tears of our own children, crying out mama ven, mama come—the call of God. And we do our best to respond, to surround them with the same love we do our own. I am glad our church is one of thousands across the nation trying to live out this call to love, striving to Share the Journey.

*Names have been changed for privacy.

Tim Severyn is a licensed social worker serving as the Director of Social Mission for Bellarmine Chapel, the Jesuit parish on the campus of Xavier University in Cincinnati, Ohio. He teaches as Adjunct Faculty for the Social Work and Theology Departments. He has masters degrees in Social Work from Washington University in St. Louis and in Religion, Ethics, and Politics from Harvard Divinity School.